By JOYCE SAENZ HARRIS

Staff Writer

MARSHALL – One of America’s great writers works right here – but

almost nobody knows it.

Which suits J. California Cooper just fine.

For the past seven years, Ms. Cooper has lived quietly in an

unpretentious neighborhood in the small East Texas city of

Marshall. Her house is bright green, like the tall old trees that

arch overhead.

“If you pay attention to nature, you know God loves color,” the

writer muses. “And if you were his favorite color you might be

green, because I know he loves green. Everything in the world is

green, almost.” Her smile is richly knowing, beatific as a

cafe-au-lait Buddha.

This corner of Texas has proved an oasis of peace and

productivity for Ms. Cooper. Her second novel, In Search of

Satisfaction (Doubleday), will be published in October. Her fifth

collection of short stories, Some Love, Some Pain, Some Time, will

follow in the fall of 1995.

Her previous story collections – A Piece of Mine, Some Soul to

Keep, Homemade Love and The Matter Is Life – won Ms. Cooper a

reputation as a gifted teller of tales. Her first novel, Family,

published by Doubleday in 1991, was bought by the Literary Guild

and helped to give her a wider, more mainstream audience.

But without Alice Walker, Ms. Cooper says, “this stuff could

still be sitting in the drawer.” Ms. Walker, a novelist who is

perhaps best known for The Color Purple, saw Ms. Cooper’s plays and

urged her to try writing stories. Ms. Walker then published A Piece

of Mine through her own company, Wild Trees Press.

“In its strong folk flavor, Cooper’s work reminds us of Langston

Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston,” Ms. Walker wrote. “Like theirs, her

style is deceptively simple and direct. …It is a delight to

read her stories.”

Their creator likewise is deceptively simple and direct, wearing

a veil of mystery even when she seemingly bares her soul.

She is “the ultimate pragmatist,” says daughter Paris Williams

of Oakland, Calif., who calls her mother “compassionate,

imaginative, practical and very loving in more ways than I can

describe.”

“One of the greatest compliments I ever received came from

her,” Ms. Williams adds. “She once said, `As long as I’ve known

you, I’ve never known you to be intentionally hurtful to anyone.’

“But that’s because I’m her child. That’s the kind of values

she raised me with.”

You know, I am a grown woman of some considerable character and

an excellent education. Which age, I am not going to tell you. I

mean, how important is age? Just try to live, I say, with wisdom

and concern for others. But by living this long (not too long), I

have learned a few things.

– “Friends, Anyone?” (from The Matter Is Life)

Ms. Cooper, who laughingly calls herself “a semi-recluse,” is

intriguingly eccentric. She writes her stories in bed, in longhand,

usually in the early-morning hours. She says she is “a bed-crazy

person,” and that writing by hand “is the only way I can get these

people (the characters’ voices) to come.” Later, she will “fill out

the skeleton” of narrative as she transfers her work to a computer,

to be printed out in manuscript form.

“I don’t know how to write,” she says disarmingly. “I just do

it.”

Her occasional public readings are vivid events marked by a

natural flair for drama, and she can hold a cafeteria full of

restless high-schoolers spellbound. But she doesn’t go out of her

way to seek publicity, preferring to let the media find her – when they can.

She’ll talk about her work while letting many things about

herself and her personal history remain deliberately vague. “She

guards her privacy,” says her daughter.

For example, Ms. Cooper appears 60-ish – but “a woman who will

tell her age will tell anything,” she quotes with a laugh. Her

years show in the tranquil, seen-it-all lines around her lively

eyes. But her hands are amazingly smooth and youthful, like those

of a 25-year-old.

Her given name, Joan, now is shortened to the initial “J.” Ms.

Cooper doesn’t usually reveal what the “J” stands for, but Alice

Walker mentioned it in the introduction to A Piece of Mine. The

adopted name “California” is after her home state; she spent most

of her life in Oakland, Berkeley and the San Francisco Bay Area.

But her father, Joseph C. Cooper, came from Marshall, and when

she was 12, she spent a year in his hometown, living with an aunt.

Later, Ms. Cooper often returned to visit. Thus she has never

forgotten her Texas roots or the gritty realities of country life,

such as picking cotton for a penny a pound.

Ms. Cooper wrote 17 plays before publishing any of her fiction,

and she was named San Francisco’s Black Playwright of the Year in

1978 for Strangers. In 1988, she was given the James Baldwin Award

and the American Library Association’s Literary Lion Award.

In 1989, Ms. Cooper won an American Book Award for Homemade

Love, and the honor brought her a flood of attention. Some of it

was the sort most struggling writers would kill to get, but much of

it she found exasperating.

It was “the only time I’ve seen her become disagreeable,” says

Reid Boates, the New Jersey literary agent who has represented Ms.

Cooper for the past eight years. “A private atmosphere is very

important to her.”

“When you win an award, all kinds of people want to talk to

you,” says Emma Rodgers, co-owner of Black Images Book Bazaar in

Oak Cliff’s Wynnewood Village. “They take your time – and your time

belongs to you and no one else.”

By 1987, Ms. Cooper had already lit out for the territory: “I

think she idealized the country life,” her daughter says. At any

rate, Ms. Cooper found solace and more of the solitude she craved

in East Texas.

Her place was goin to be nice. She furnished it with the best of

things, tho she never lowed no one in them special rooms. She

didn’t much go in em herself cept to go sit and look round at what

was hers. Hers.

– from Family

In Marshall, California Cooper lives in an idiosyncratic,

inconspicuous but densely textured sanctum of her own devising.

Here, she has her pair of goldfinches and her two cats: one

neurotically shy to the point of invisibility, one aggressively

sociable. She also has eight chickens, all named, who provide her

with fresh eggs to eat and give away. She surrounds herself with

shelves of books and music, with hanging plants, manuscripts and

works of art in progress.

This is her world, but be warned: The welcome mat is not out.

She doesn’t mind the occasional public reading, book-signing or

a good chat over lunch in town. Occasionally she will sit and visit

in the shade of her trees. But she rarely invites guests into her

home, and she discourages drop-ins.

“I DON’T WANT ANY COMPANY,” she says sternly.

She says visitors disturb her “vibes,” the quietude that lets

her listen to the vivid characters’ voices inside her head. Even

her chickens or her old pecan tree, she says, can tell her a story.

Hers is a creative process that can best be described, perhaps, in

one word: “organic.”

“The stories arrive full-blown,” says Mr. Boates. “That’s their

magic, really.

“Her writing process is listening to her characters, and it’s a

very special way of working. That’s what lets her write in the

voice of a cocky, narcissistic young man in one story, and in the

next as an old woman, remembering some incident with her daughter

50 years ago.”

Says Ms. Rodgers, “She talks like people talk.”

Oh, and how her characters do talk.

Vigorous, melancholy, malicious, tormented, joyful, nostalgic,

headstrong, and most of all human – California Cooper’s people talk

like real folks.

Her mostly first-person narratives flow “partly from experience

and partly from observing,” says her daughter, Ms. Williams. A

typical Cooper story is like a parable whose moral often can be

summed up: What goes around, comes around.

In Ms. Cooper’s universe, evil is punished, “integrity always

triumphs,” and the eternal verities – God, love, family, justice –

stand in stark contrast to human foolishness and conceit.

When her characters do or say thoughtless things, Ms. Cooper

says, “I love it, because I don’t like a fool. I really don’t like

a fool! All my life I’ve prayed, `Don’t let me be a fool.’ ”

She likes people with get-up-and-go. “Make a mistake,” she says

firmly. “But let it be a mistake where you’re reaching and you just

reached a little too high.”

However folksy her stories might be, there is nothing naive or

innocent about them. They can be funny, sensual or uplifting – but

they may also make a reader squirm. In the story titled “Vanity,”

for example, a beautiful woman’s narcissism leads her into a life

of utter degradation, rendered in grim, unflinching detail.

And her characters’ tragedies become her own. “Me, when I get a

chance to cry, I cry,” Ms. Cooper admits. “I cry at my own stories,

right on the stage. I try not to, but when I’m reading, I hurt.”

She cries when she writes her stories, too, “because I’m living

them.”

Ms. Cooper’s previous novel, Family, portrays that most American

of institutions in a struggle to survive. The saga begins with

Clora, the matriarch, a woman born into slavery. Despair drives

Clora to suicide, and the book is told by the voice of her spirit,

watching over a beloved daughter named Always.

While Family is in a sense more Always’ story than her mother’s,

it is Clora’s voice, disembodied and eternally weary, that echoes

in the reader’s mind:

Some people say we was born slaves . . . but I don’t blive that.

I say I was born a free human being, but I was made a slave right after.

Ms. Cooper says she is proud to be who she is, a black woman who

has prevailed. But she also believes, as the title of one of her

Homemade Love stories puts it, that “happiness does not come in

colors.”

Neither does kindness or goodness, evil or misery. Though her

narrators most often speak in the vernacular of black America,

there is no color line drawn between Ms. Cooper’s heroes and her

villains. Family’s story of Clora, Always and their kin is a

universal one, encompassing not only the African-American

experience but the family of mankind.

Family is “the nucleus of life,” Ms. Cooper says. “If you think

about it, what else is there in the world?”

You know, I’m just a kid, but I got nerves, and sometimes

grown-up people just really get on em! Like always talkin about how

kids don’t have no sense “in these days.” Like they got all the

last sense there was to get. Everybody with some sense knows that

if grown-up people had so much sense the whole world wouldn’t be in

the shape it’s in today!

– “How, Why to Get Rich” (from The Matter Is Life)

It all started with paper dolls.

Maxine Rosemary Lincoln Cooper – “Mimi” – was an independent

woman who “wanted to be a pioneer or a gun moll.” Mimi’s youngest

girl was known as the one who made up stories. She put her cast of

paper dolls into homemade plays, creating drama from pure

imagination.

Which was adorable at age 6 or 8 – but at 18?

Mimi appreciated her daughter’s lively imagination, but enough

was enough. You are too oooold for this! she ruled. Time to put

away childish things, like those paper dolls.

“My mother took them away,” Ms. Cooper says. “But the next year

I was married and was getting ready to have a baby.

“She should have left me alone with those paper dolls! But she

took them away – and so I began to write stuff out.”

She had always loved fairy tales. “Imagine a diamond mountain

and a lemonade lake and a golden apple!” Ms. Cooper marvels. “Who

would think of a pea under a mattress?”

Real life, of course, didn’t always have a happy ending. Ms.

Cooper “was married a couple of times, but they’re dead.” But if

marriages did not last, motherhood did. So “my child,” as she

affectionately calls Paris in the dedication of every book, is her

pride and joy.

Ms. Cooper is possessed of both earthy practicality and a

certain childlike ability to live in her imagination. “And I am the

most grateful person in the world that I haven’t lost it,” she says.

“People used to say, when I was grown and had a daughter, `She

just crazy. She ain’t never gonna grow up.’ Because the way I

thought and the way I acted – I carried my daughter around in my

bicycle basket! She never got hurt; we did fine. But lots of things

I did, people thought they were juvenile.

“They were not juvenile,” Ms. Cooper says softly. “They were

innocent, I think.

“And I still like paper dolls.”

My mama say Time is like an ocean tide. It just keep rollin on,

bringin new things for a person to try to sift through. You don’t

never know what’s comin! Or what ain’t comin!

– “Sisters of the Rain” (from Some Soul to Keep)

California Cooper “is probably the pre-eminent African-American

short story writer today,” says John R. Posey of Fort Worth,

publisher of The African American Literary Review. “She seems to

have a way of connecting her characters to African-American women

all over the United States today.

“She gets huge turnouts for her readings,” Mr. Posey adds. He

recalls that at one such event at Black Images Book Bazaar, “I was

one of maybe five men there. …She’s a legend among African-American female readers in Texas.”

Indeed, Emma Rodgers says that until Terry McMillan’s Waiting to

Exhale came along, Ms. Cooper was the best-selling author at Black

Images. Ms. Cooper’s work now is being anthologized, is turning up

in American high school and college literature courses, and is read

and respected in Europe.

Fame and success have their uses, because they allow Ms. Cooper

the freedom to arrange her life as she chooses. What she does not

like is the assumption that success makes her a public property.

“I meet a lot of people who want to hug me and kiss me,” she

says. “You cannot hug and kiss all these people. What makes them

think that – that you belong to them?”

She remembers walking down a hallway at her publisher’s and

seeing Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, a Doubleday editor, coming

toward her. “I had on some black pants and a pretty orange knit

sweater, and she looked me up and down in a split second,” Ms.

Cooper reminisces. “Then she looked at my face, and she smiled. I

saw her, and I smiled and nodded, and we kept going.”

Yes, she would have loved to meet Mrs. Onassis. But that’s the

kind of fandom Ms. Cooper prefers: respectful, not presumptuous,

not overly familiar.

She is humbly grateful, she says, for every reader who enjoys

her work. But owning California Cooper’s books, it is clear, does

not mean owning her.

“Nobody really knows me,” she says softly, “and I’ll tell you

why. Because I am really extra special private for some reason I

don’t know.

“My daughter knows me more than anybody. But I don’t know of

anybody else, except my mother, and she’s not alive.” Her voice

drops down, sadly: “Oh, I hate that. Now, when I have enough money

to take her somewhere.”

Ms. Cooper has dealt with many losses in her life, the most

recent being that of her only brother last January. But “her

biggest, most important loss was her mother,” says her daughter,

Ms. Williams. “She’ll never get over that. It’s been about 12

years, and it’s still a very big wound for her.”

Time’s passage is an essential element in Ms. Cooper’s art. She

is acutely aware of the encroachments of age. “I just hate to see

this time pass,” she frets.

She has done much in her life – traveled the world, reared a

child, worked as a manicurist, a waitress, a secretary, a loan

officer. She says she even joined the Teamsters and drove buses and

trucks in Alaska. “Oh, what a place, what a place! Mountains,

mountains, just glaring in the sunlight – diamonds, diamonds! And

just as pure and clear.”

She loves to tell stories, but she likes to do, too. “I don’t

believe people hate to grow old so much as you hate to grow past

your opportunities,” Ms. Cooper says. “The way life looks to me is,

you can do different chapters.”

In her next “chapter,” she plans to move back to Oakland for at

least part of each year, to be closer to her daughter. And she

doesn’t plan to be writing books forever, because she wants to do

so much more: take art classes and learn to paint pictures. Perhaps

even train as a practical nurse and take flying lessons, so that

she can take medical care to people in remote places of the world.

Meantime, she stays tuned in to the follies of the human heart,

observing, laughing, wondering and always aware.

“I tell people: You’d better watch what’s going on around you,”

Ms. Cooper says. “Because this is life.”

For the first decade of his career as a writer, British novelist Ken Follett was widely known as a master of the thriller genre, with best-selling novels of the late 1970s and early ’80s such as Eye of the Needle and The Key to Rebecca. Then he surprised everyone in 1989 with The Pillars of the Earth, an ambitious and wildly popular historical epic set in the Middle Ages in the fictional English town of Kingsbridge.

For the first decade of his career as a writer, British novelist Ken Follett was widely known as a master of the thriller genre, with best-selling novels of the late 1970s and early ’80s such as Eye of the Needle and The Key to Rebecca. Then he surprised everyone in 1989 with The Pillars of the Earth, an ambitious and wildly popular historical epic set in the Middle Ages in the fictional English town of Kingsbridge. The third Kingsbridge entry, A Column of Fire (Viking, $36), is set in the Elizabethan era and will be published Sept. 12. This time, religious intolerance is barely held in check as great empires clash, naval underdogs triumph, and the art of spying flourishes along with romance, adventure and betrayal.

The third Kingsbridge entry, A Column of Fire (Viking, $36), is set in the Elizabethan era and will be published Sept. 12. This time, religious intolerance is barely held in check as great empires clash, naval underdogs triumph, and the art of spying flourishes along with romance, adventure and betrayal.

ans can hear her speak Feb. 7 at Barnes & Noble on Northwest Highway as she gears up for a multicity book tour. She spoke with us first, from her historic Craftsman cottage, which she shares with with a husband, three cats and “two very demanding German shepherds.”

ans can hear her speak Feb. 7 at Barnes & Noble on Northwest Highway as she gears up for a multicity book tour. She spoke with us first, from her historic Craftsman cottage, which she shares with with a husband, three cats and “two very demanding German shepherds.”

For readers of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes tales, London in 1885 is a long-cherished fantasy destination. Doyle’s narrator, Dr. John Watson, referred to the London of that period as “that great cesspool into which all the loungers and idlers of the Empire are irresistibly drained.” Yet we think longingly of pea-soup fogs and hansom cabs and wish we could somehow experience them firsthand.

For readers of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes tales, London in 1885 is a long-cherished fantasy destination. Doyle’s narrator, Dr. John Watson, referred to the London of that period as “that great cesspool into which all the loungers and idlers of the Empire are irresistibly drained.” Yet we think longingly of pea-soup fogs and hansom cabs and wish we could somehow experience them firsthand. Canadian poet Steven Price’s second novel, By Gaslight, is a dark Victorian thriller that will put paid to such fancies. If you loved big, atmospheric period mysteries such as Charles Palliser’s The Quincunx or Caleb Carr’s The Alienist, here is a novel with similar hypnotic qualities. By Gaslight draws in and magically transports the reader, as if by time machine, to another world.

Canadian poet Steven Price’s second novel, By Gaslight, is a dark Victorian thriller that will put paid to such fancies. If you loved big, atmospheric period mysteries such as Charles Palliser’s The Quincunx or Caleb Carr’s The Alienist, here is a novel with similar hypnotic qualities. By Gaslight draws in and magically transports the reader, as if by time machine, to another world.

However, her new book,

However, her new book,

Two women, both closely identified with the American abolitionist movement, wrote enormously influential best-sellers in the mid-1800s. The first, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s anti-slavery epic Uncle Tom’s Cabin, is acknowledged as a philosophical precursor to the Civil War, but it is barely read today except by scholars of 19th-century literary feminism.

Two women, both closely identified with the American abolitionist movement, wrote enormously influential best-sellers in the mid-1800s. The first, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s anti-slavery epic Uncle Tom’s Cabin, is acknowledged as a philosophical precursor to the Civil War, but it is barely read today except by scholars of 19th-century literary feminism.

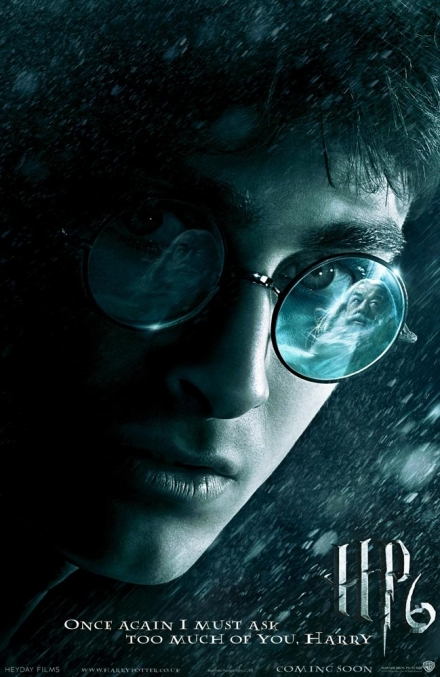

Number six in the series is the darkest yet, as the boy wizard’s fan base surely knows. It pays a good deal of attention to certain key aspects of the J.K. Rowling book, while other parts of the original story, as always, must fall by the wayside — even with a running time of two and a half hours, something’s gotta go.

Number six in the series is the darkest yet, as the boy wizard’s fan base surely knows. It pays a good deal of attention to certain key aspects of the J.K. Rowling book, while other parts of the original story, as always, must fall by the wayside — even with a running time of two and a half hours, something’s gotta go.